I want to learn...

Welcome to the world of German grammar rules! While some people love the intricacies and rules of grammar, others find it daunting. If you fall into the latter category, try to think of it as a linguistic adventure, with grammar rules serving as your trusty map guiding you forward.

Whether you're a language geek or just trying to pick up some basic German grammar, this article will teach you about the most important German grammar rules. We’ve got some basic hacks for beginners as well as tips for advanced learners who want a refresher. So let’s get started, as we spill the beans on our top five basic German grammar rules that will help progress quickly in German.

German grammar rule 1: Noun genders

Alright, language adventurers, we’re stepping into the world of German noun genders. In German, nouns can be complex. But don’t worry, we’ll provide you with some hints to help you on this journey. Unlike English, which doesn't have grammatical genders for nouns, German comes up with three genders – masculine, feminine and neuter. This affects the use of the definite (the) and indefinite (a/an) articles in German. Let’s take a look at three examples:

German noun gender with definite and indefinite articles

| Gender | Definite article | English translation | Indefinite article | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | der Tisch | the table | ein Tisch | a table |

| Feminine | die Sonne | the sun | eine Sonne | a sun |

| Neuter | das Haus | the house | ein Haus | a house |

You see that German nouns have three different articles for the (der, die, das) and two fora/an (ein, eine). Learning the gender of each noun largely hinges on memorization. However, there are a few German grammar hacks that can help. Let’s take a look at some gender patterns.

Masculine, Feminine, Neuter: Decoding the German gender patterns

If the person is masculine, the article is masculine: der Mann (the man), der Vater (the father), der Bruder (the brother)

If the person is feminine, the article is feminine: die Frau (the woman), die Mutter (the mother), die Schwester (the sister). One important exception is here das Mädchen (the girl) which has the neuter article.

Times of the day, days of the week and months are always masculine: der Morgen (the morning), der Abend (the evening), der Montag (the Monday), der Dienstag (the Tuesday), der Januar (the January), der Februar (the February)

As well as these three basic German grammar rules for noun genders, there are also some common word endings that indicate feminine and neuter nouns.

German common word endings that indicate feminine and neuter nouns

| Feminine endings | German example | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| -ung | die Warnung | the warning |

| -heit | die Freiheit | the freedom |

| -keit | die Flüssigkeit | the liquid |

| -ion | die Information | the information |

| -schaft | die Mannschaft | the team |

| -ät | die Universität | the university |

| Neuter endings | ||

| -um | das Museum | the museum |

| -chen the girl | das Mädchen | the girl |

| -lein | das Kindlein | the (little) child |

The last two examples “-chen” and “-lein” are called diminutives. Adding them to the end of a noun can "diminish" them, or make them softer. It is similar to the English way of saying “Mommy” for Mum, “Daddy” for Dad, and “Aunty” for Aunt.

With these German grammar rules, you've already cracked a big part of the German gender code. Nouns ending in -ung or -heit are feminine and -um or -lein are neuter.

Of course, there are always exceptions, we’re talking about grammar rules after all, so don’t worry if you don’t know all the articles immediately. Just try to memorize a few of these rules and endings and you’ll be off to a good start.

German grammar rule 2: German word combinations

Let’s continue this adventure as we dive into the wild world of German compound nouns. What makes compound nouns so wild? German has a magic trick, it can join two nouns together to create a new descriptive and precise word. For example:

der Schlüssel (the key)

A pretty simple word. We use ein Schlüssel to open and close a door, a cage, etc. So now if we want to express that this is a key for a door, you would simply say:

der Türschlüssel (the door key)

You see what we did here? We just blended both nouns Tür (door) and Schlüssel (key) together without a space. This simple act allows us to specify which kind of key we’re talking about. The last noun in a compound noun is always the basic meaning of the entire word, the one(s) at the start are more specific.

We can go on like this and add another word at the front to specify the exact kind of door:

der Haustürschlüssel (the house door key)

der Autotürschlüssel (the car door key)

Again, notice there are no spaces between the nouns. These long words might seem overwhelming in the beginning, so here’s the trick. If you see a compound noun in the wild, tame it by breaking it down into its individual components. This way, you can identify the meanings and pronunciations of the root words and thus the whole compound noun. Eg:

das Haus (the house), die Tür (the door), der Schlüssel (the key)

Did you notice the gender? The gender of the whole word is always determined by the gender of the last noun. In the case of der Haustürschlüssel, you can see above that every single noun has a different gender. But the compound noun of the three of them is masculine since the last component Schlüssel is masculine so we say der/ein Haustürschlüssel. Let’s check out some more examples:

das Hotelzimmer (the hotel room)

die Schreibtischlampe (the desk lamp)

die Sporthose (the sports pants)

die Kaffeetasse (the coffee mug)

der Kinoabend (the movie night)

German grammar rule 3: German time with Präsens and Perfekt

In German, the tenses Präsens (simple present) and Perfekt (present perfect) are really handy for everyday talk. Concentrating on mastering the Präsens and Perfekt tenses will significantly enhance your communication skill quickly. Even though there are other tenses in German, Präsens and Perfekt are like the MVPs for everyday communication.

Präsens is great for talking about what's happening now, daily routines, and general truths as well as expressing action in the future which makes it a very versatile German tense. It’s also straightforward and clear, making it perfect for everyday communication. Perfekt comes in when you're talking about things that happened in the past.

In German, we have six different subjects, each with their respective endings. The verb changes to match the subject of a sentence. Thankfully, most German verbs are regular and follow a predictable conjugation pattern. The three regular verb conjugations are categorized by their infinitive endings: -en (eg: machen, schwimmen), -eln (eg: sammeln, klingeln), -ern (eg: ändern, klettern).

German conjugation (Präsens)

| Personal pronoun | machen (to make) | sammeln (to collect) | ändern (to change) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ich (I) | mache | sammle | ändere |

| du (you) | machst | sammelst | änderst |

| er/sie/es (he/she/it) | macht | sammelt | ändert |

| wir (we) | machen | sammeln | ändern |

| ihr (you) | macht | sammelt | ändert |

| sie/Sie (they/you) | machen | sammeln | ändern |

Let’s see the Präsens in some examples:

Ich mache Hausaufgaben. (I’m doing homework.)

Du machst Hausaufgaben. (You’re doing homework.)

Er sammelt Briefmarken. (He collects stamps.)

Wir sammeln Pilze. (We’re collecting mushrooms.)

Ihr ändert den Plan. (You change the plan.)

Sie ändern ihre Reise. (They change their journey.)

German conjugation Perfekt

Now let’s look at these phrases in the past. In Perfekt (e.g. I have done), you also need to choose your auxiliary verb haben (to have) or sein (to be). In the vast majority of cases, you need haben. Sein is mostly used for motion verbs (to walk) or if you have a change of state (to freeze). So let's start by covering the fundamental forms of haben and sein:

German conjugation (Perfekt)

| Personal pronoun | haben (to have) | sein (to be) |

|---|---|---|

| ich | habe | bin |

| du | hast | bist |

| er/sie/es | hat | ist |

| wir | haben | sind |

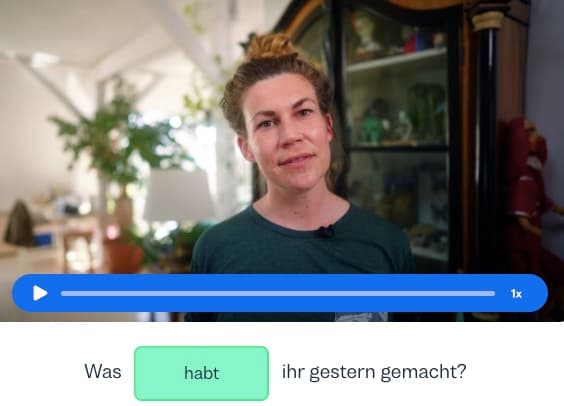

| ihr | habt | seid |

| sie/Sie | haben | sind |

To create the past participle of the verb you would like to use in the past, regular verbs adhere to a straightforward pattern:

append "ge-" to the infinitive stem and "-t", e.g.: machen (to make) – gemacht (made)

For irregular verbs that change their verb stem or vowel within the infinitive stem:append "ge-" to the verb stem and "-en", e.g.: gehen (to go) – gegangen (gone).

With this, you can express a lot of actions in the past in German:

Ich habe meine Hausaufgaben gemacht. (I have done my homework.)

Du hast deine Hausaufgaben gemacht. (You have done your homework.)

Er hat Briefmarken gesammelt. (He has collected stamps.)

Wir haben Pilze gesammelt. (We have collected mushrooms.)

Ihr habt den Plan geändert. (You have changed the plan.)

Sie haben ihre Reise geändert. (They have changed the journey.)

These are the important basic German grammar rules for the present and past tense. Check out the tenses in more detail here.

Let’s jump to the next chapter and take a look at sentence structure.

German grammar rule 4: German sentence structure

German sentence structure is a bit different to English, but once you get the hang of it, it does make sense, we promise! So let's break down the basics of German sentence structure.

First of all, it’s all about the verb position in German. The verb is the main character of the sentence. If you can put it in the right position, you will be able to create sentences correctly. In a regular German sentence, you often find a Subject-Verb-Object structure, which is similar to English. The subject, who or what the sentence is about, comes first, followed by the verb (the action), and then the object (the receiver of the action). For example:

Ich esse einen Apfel. (I am eating an apple.)

Simple phrases like this are very similar to English. But unfortunately, we can’t only speak in simple phrases. In advanced German grammar structure, conjunctions play a big role.

If you combine two sentences with the German conjunctions und (and), aber (but) and oder (or), the verb stays in its normal sentence position. For example:

Ich höre gern Musik und ich lese gern. (I like listening to music and I like reading.)

Ich arbeite heute, aber ich habe am Abend Zeit. (I am working today but I have time tonight.)

Ich gehe ins Kino oder ich bleibe zu Hause. (I go to the cinema or I stay at home.)

So far, it’s pretty similar to English. But here's the cool part – German is flexible. Keep an eye on elements like time, manner, and place in a sentence. They often pop up before the main verb. In this case, you switch the verb and the subject so that the verb always stays in the second position of the sentence. Let’s look at an example:

Morgen spiele ich Fußball (Tomorrow, I play football).

The information about the time – morgen (tomorrow) – comes before the verb. While English keeps the same position of subject (I) followed by the verb (play), in German the conjugated verb (spiele) claims its position at number two so that the subject (ich) follows the verb now.

In yes/no questions, the verb comes before the subject as well:

Trinkst du Kaffee? (Are you drinking coffee?)

Bist du zu Hause? (Are you at home?)

Spielst du ein Instrument? (Do you play an instrument?)

Now let’s have a look at the Perfekt tense. German sentence structure in the Perfekt tense is not rocket science. Even though it’s different from English, it actually follows a very logical pattern.

When constructing a sentence, you kick things off with the subject. Next, the auxiliary verb either haben or sein, takes the second position. The grand finale will always be the past participle. But wait, there's more… When you sprinkle in some extras like direct objects, indirect objects, or information about time, manner, place, they all come between the auxiliary verb and the past participle. For example:

Ich habe gestern einen Film gesehen. (I watched a movie yesterday)

Wir sind heute Morgen ins Kino gegangen. (We went to the cinema this morning).

So, there you have it, German sentence structure in the Perfekt tense. While every sentence is a bit of a linguistic puzzle, it does follow a logical pattern.

In a nutshell, German sentence structure is a bit like English, but with its own twist. Embrace the flexibility, and you'll not only speak grammatically correct German but also add a bit of flair to your language. So don’t be afraid of German sentences, simply learn the patterns, and let the language's rhythm guide your communication!

German grammar rule 5: Powerful German modal verbs

German modal verbs play a crucial role in expressing attitudes, abilities, and possibilities. These versatile verbs allow speakers to convey meanings with precision. At the heart of German modal verbs are:

können (can)

dürfen (may)

wollen (want)

müssen (must)

sollen (should)

German modal verb conjugations

| Personal pronoun | können (can) | dürfen (may) | wollen (want) | müssen (must) | sollen (should) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ich | kann | darf | will | muss | soll |

| du | kannst | darfst | willst | musst | sollst |

| er/sie/es | kann | darf | will | muss | soll |

| wir | können | dürfen | wollen | müssen | sollen |

| ihr | könnt | dürft | wollt | müsst | sollt |

| sie/Sie | können | dürfen | wollen | müssen | sollen |

Each of these verbs adds a little nuance to sentences, expressing the speaker's view on an action or situation. Understanding the sentence structure when using these verbs is the key to rocking your German conversation skills.

Modal verbs always claim the second position of the sentence. But here’s the trick: When you use a modal verb, you need to use another verb in its infinitive form. Take a look at the following example:

Ich kann schwimmen. (I can swim)

The modal verb “kann” is followed by the infinitive form of swim “schwimmen”. It’s exactly the same as English, easy right? Not so fast! If you add more information to your sentence, the main verb in infinitive form always appears at the end of the sentence. Check out the following examples:

Ich kann Deutsch sprechen. (I can speak German.)

Ich muss am Wochenende meine Hausaufgaben machen. (I have to do my homework on the weekend.)

Ich will nächstes Jahr nach Österreich reisen. (I want to travel to Austria next year.)

And for a bit of spice, throw in nicht (not) to the mix after the modal verb to negate a statement, like:

Ich kann nicht schwimmen. (I cannot swim.)

Ich will nicht ins Kino gehen. (I don’t want to go to the cinema.)

Now, when it comes to questions, modal verbs steal the spotlight, coming right at the beginning of the sentence. For example:

Kannst du Deutsch sprechen? (Can you speak German?)

Willst du heute Abend ins Kino gehen? (Do you want to go to the cinema tonight?)

Musst du deine Hausaufgaben machen? (Do you have to do your homework?)

These versatile verbs aren't just about expressing ability, necessity, or permission – they're the secret sauce that adds flavor to your conversation. Simply keep an eye on their moves, and you'll be crafting sentences like a pro with German modal verbs.

Now you know the 5 basic German grammar rules

With our top 5 grammar rules, you’ve got the ticket to following the twists and turns of German grammar – no more mysteries about articles, word combinations, or word order. Whether you're a language geek or just trying to get the hang of it, these basic rules are the keys to mastering German.

So, armed with these tips, it’s time to continue your German language journey with confidence.

AUTHOR

Mathias Neubauer

Newlanguages