I want to learn...

In Italian, passato prossimo corresponds with both the simple past (“I did”) and the present perfect (“I have done”) in English. It is among the most used past tense in Italian, and we use it to talk about completed actions in the past.

Passato prossimo is made up of two parts: an auxiliary verb and the past participle of the main verb. If this sounds overwhelming, don’t worry. Today we’ll learn how to use passato prossimo with examples so you can have it mastered in no time.

When to use passato prossimo?

We can use this tense when we’re talking about the past. Passato prossimo indicates an action happened recently or is still relevant, so it’s “close” to the present. It also signals that the action has started and finished by the time of speaking. Sometimes, it describes sudden or interrupting actions.

Take a look at these examples:

Ho visto quel film la settimana scorsa. (I saw that film last week.)

L’anno scorso Anna ha visitato il Giappone. (Last year Anna visited Japan.)

Note: Watch out—there is more than one past tense in Italian. Another common past tense is the imperfetto or imperfect tense. That tense is used for talking about a habitual or continuous action that happened in the past. It looks like this: “Ero una bambina” (I was a baby) or “Non lo sapeva” (He didn’t know.) Knowing which past tense to use will become more intuitive with practice and time.

You’ll often find

Ieri (yesterday)

Ieri sera (last night)

Recentemente (recently)

Due ore fa (two hours ago)

La settimana scorsa (last week)

Un mese fa (a month ago)

Un anno fa (a year ago)

How do you form passato prossimo?

In Italian, passato prossimo is a compound tense, meaning it’s made with two parts:

The auxiliary (either essere or avere) + a past participle

Here’s an example:

Ho mangiato. (I ate/I have eaten.)

In the case above, ho is the auxiliary conjugated for io (I), while mangiato is the past participle of mangiare (to eat).

The auxiliary is usually avere (to have) in the present tense. The chart below shows the full conjugation of presente indicativo (present tense) for this verb.

The present tense of avere (to have)

| Italian pronoun | Conjugated form of avere |

|---|---|

| io I | ho have |

| tu you | hai have |

| lui/lei he/she | ha has |

| noi we | abbiamo have |

| voi you plural | avete have |

| loro they | hanno have |

Remember, the letter “h” is silent, so you will pronounce “ha,” “hai,” “ha” and “hanno” without the “h” sound.

Italian past participles

In general, the way to know the past participle of any verb is to take off the last three letters (-are, -ere or -ire) and replace them with-ato, -uto or -ito:

Mangiare -> mangiato

Parlare -> parlato

Temere -> temuto

Cadere -> caduto

Dormire -> dormito

Sentire -> sentito

Of course, there are some verbs that won’t follow this rule. Some common irregular past participles are:

Vedere -> visto (to see)

Fare -> fatto (to do/make)

Dire -> detto (to say)

Leggere -> letto (to read)

The auxiliary will change according to the subject who did the action, but the past participle doesn’t change. Have a look at some more examples with mangiare.

(Io) Ho mangiato una mela. (I ate an apple).

(Tu) Che cosa hai mangiato? (What did you eat?)

(Lei) Ha mangiato la pasta. (She ate the pasta.)

(Noi) Abbiamo mangiato al ristorante. (We ate at the restaurant)

(Voi) Quando avete mangiato? (When did you all eat?)

(Loro) Sara e Andrea hanno mangiato a casa. (Sara and Andrea ate at home.)

There you have it! That’s the pattern for past tense verbs that take avere as their auxiliary. But hold on, because it can get tricky. Some verbs don’t take avere as their auxiliary—instead, they take essere (to be).

Passato prossimo with essere (to be)

Most Italian verbs will use avere as their auxiliary. But some verbs are different and will use essere instead.

Generally, these verbs are verbs of movement or state of being. Here’s a list of the most common ones that use essere:

Andare (to go)

Arrivare (to arrive)

Tornare (to return)

Essere (to be)

Stare (to stay)

Entrare (to enter)

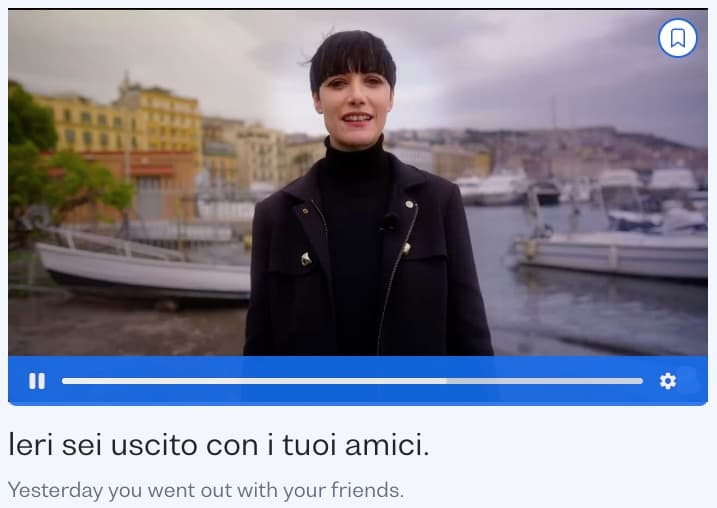

Uscire (to go out/to leave)

Partire (to leave for)

Diventare (to become)

Salire (to go up) (when used intransitively)

Scendere (to go down) (when used intransitively)

Nascere (to be born)

Venire (to come)

The formula is the same as before: auxiliary (conjugated in the present tense) + the past participle of the verb.

Have a look at the table below for how to conjugate essere in the present tense.

The present tense of essere (to be)

| Italian pronoun | Conjugated form of essere |

|---|---|

| io I | sono am |

| tu you | sei are |

| lui/lei he/she | è is |

| noi we | siamo are |

| voi you plural | siete are |

| loro they | sono are |

The past participles for verbs that take essere follow the same rule as verbs that take avere:

Andare -> andato

Cadere -> caduto

Uscire -> uscito

There are some verbs that take essere and have irregular past participles, for instance:

Essere -> stato (to be)

Nascere -> nato (to be born)

Venire -> venuto (to come)

Scendere -> sceso (to go down)

One last rule regarding verbs that take essere

If a past tense verb takes essere as its auxiliary, no matter whether it’s regular or irregular, it will change according to the number (plural or singular) and gender (masculine or feminine) of the subject (io, noi, tu, etc.)

For example:

Sono stato = (I have been, singular masculine)

Sono stata = (I have been, singular feminine)

Siamo stati = (We have been, plural masculine)

Siamo state = (We have been, plural feminine)

There are four possible endings for these verbs:-o for one male, -a for one female, -i for a male or mixed gender group, and -e for a female group.

Take a look at the example sentences below that demonstrate this rule:

(One male) Io sono stato in Italia. (I have been to Italy.)

(One female) Maria è stata in Italia. (Maria has been to Italy.)

(Male group) Siete andati in questo ristorante? (Have you gone to this restaurant?)

(Mixed gender group) Siete venuti in piscina. (You have come to the pool.)

(Female group) Le ragazze sono andate a scuola a piedi. (The girls went to school on foot.)

This rule applies to people as well as all feminine and masculine nouns—whether they’re people, animals or objects:

Il pacco è arrivato stamattina. (The parcel has arrived this morning.)

Tutti i treni sono partiti in orario. (All the trains left on time.)

Newlanguages